If you’ve searched for advice on how to structure a story, it’s a good bet that you’ve heard the name John Yorke. A writer, script editor, and television producer, Yorke’s Into the Woods is a treatise on how to tell great stories, applying Yorke’s own experience and research to the tenets of storytelling laid out in Joseph Campbell’s seminal The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Whether you’re writing book, a play, a TV show, or a movie, Yorke has things to tell you.

All of Yorke’s (pretty short) book is worth your time, but it’s his theory of fractal storytelling and incremental change that’s particularly groundbreaking, so that’s what we’ll be looking at in today’s article.

The story circle

Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces is, in part, a comparative study of popular mythologies (and number 10 on our list of The Top Ten Books On Writing That’ll Make You A Better Writer). While Campbell’s findings have often been applied beyond their remit, his most famous suggestion was that many of the world’s most enduring stories follow a circular story structure, with the hero answering a call to adventure, crossing the threshold of the unknown, facing their lowest moment, transforming, atoning for their misdeeds, and returning to the world they know as a new person, forever changed.

It’s a structure that academics have applied to everything from The Odyssey and Hamlet to Star Wars and The Wizard of Oz. While Campbell’s suggestion isn’t that this is true of every story, it’s definitely a structure the human brain finds satisfying, and one we can see again and again in history’s most beloved, most long-lived tales. Of course, there’s a lot more to Campbell’s theorizing, but that’s the basic grounding we need to discuss how Yorke builds on his ideas.

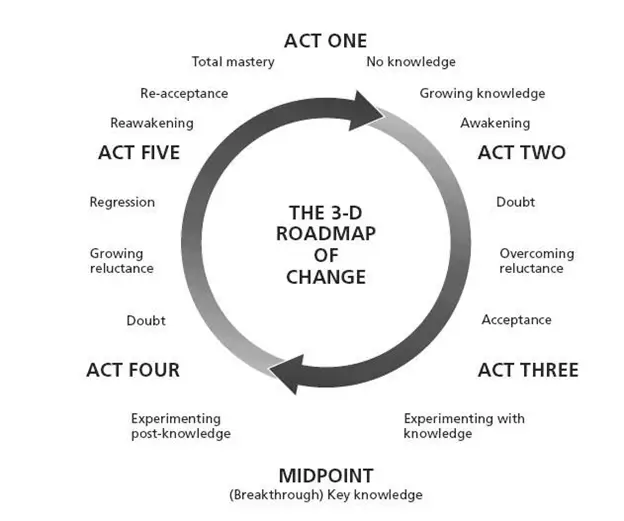

In Into the Woods, Yorke discusses breaking stories into five acts. Each of these acts is broken down into three key moments, echoing the structure of Campbell’s hero’s journey. Yorke calls this the ‘Roadmap of Change.’

Key to understanding both Yorke’s roadmap and Campbell’s hero’s journey is the idea that we’re focusing on the journey of a single, central character. Of course, they can be expanded beyond that, but it’s useful to keep in mind, when looking at the diagram above, that it describes a story in terms of the protagonist’s journey from regular schmo to triumphant hero.

So, those are the basics of Yorke’s approach, but what makes it so special?

Incremental change

One of the chief virtues of Yorke’s theory is his approach to change. While many people describe character arcs in terms of whole stories, Yorke instead approaches them as the end result of repeated, incremental change.

In this way, Yorke’s protagonists don’t learn one big lesson – they keep learning the same lesson in different ways, with the stakes increasing up until the point where the protagonist has to demonstrate what they’ve learned (and learned, and learned) in order to solve the largest expression of their problem.

This approach to character growth has many advantages. The first is that it’s pretty realistic – most of us don’t learn one big lesson, accomplish one big thing, and then coast for the rest of our lives. Instead, we keep coming up against tests of who we are, big and small, and the decisions we make build and build to form the person we become.

Second, this approach will help you write consistent characters. If you’re writing a character who learns one big lesson and does one big thing, it’s easy to accidentally load them down with contradictory moments. Characters learning to be selfless who never consider anyone who isn’t standing in front of them; characters learning to value and support their loved ones who do nothing but snark at them; characters learning to be independent who seem perfectly content in their dependent roles.

Part of the reason for this is that you can’t let your character meet their goal too quickly. If a character’s ultimate goal is fulfilled partway through the story, you’ve lost the thing you were building towards… or so the thinking goes. In practice, this can often lead to characters who spend so long putting off their big change that the reader starts to believe, on a basic level, that their flawed state is more authentic. For example, imagine a character whose ultimate accomplishment is showing bravery. It’s going to be a satisfying moment when it comes, but if they spend the whole story demonstrating cowardice, then it’s going to be hard for the reader to accept that they are now going to live as a brave person, as opposed to being a natural coward who performed a single act of bravery. In contrast, if that character is always getting a little braver – albeit in many different ways, so the balance doesn’t tip too early – then the transformation feels both more authentic and more enduring.

A parallel benefit of Yorke’s approach is that the same effect extends to theme and tone. Many, many books that are meant to be about a specific concept don’t actually engage with that concept in their middle sections. It’s brought up at the start, to define the hero’s arc, and then mentioned at the end, to show they’ve been successful on their journey, but it isn’t truly explored or exemplified during the meat of the story. This is often the case in stories where writers are embracing a set of values they think society supports but which they don’t personally think are that important.

As an example, think of a terrible rom-com where the male character’s arc is that he needs to be less immature and more open (The Ugly Truth, for instance). This is a character arc that society generally agrees is necessary in real life, but it’s one that few writers are passionate about communicating, and it’s especially unattractive when you’re trying to tell a fun story; a more mature character just isn’t setting up as many zany situations or outrageous one-liners, which means there’s an incentive to keep them immature right up until the moment where you need them to transform. That’s fine, but it completely undermines any cohesive theme in your story – one big moment where maturity is a virtue can’t compete against a hundred moments where immaturity was fun. In this way, you end up with a story that claims to be about one thing but is actually about another, creating a dissonance that makes it forgettable at best and irritating at worst.

In contrast, consider a film like Shaun of the Dead. This is another rom-com where the male lead’s arc is his journey to maturity, but the film introduces a gradually escalating set of circumstances where the indecisive, immature character has to take more and more responsibility for his decisions, admitting the importance of relationships he previously neglected and going from lazy do-nothing to decisive leader. The story is still compelling, there are still big moments of character transformation, and when the ending comes, it feels momentous – it fulfils a promise the entire movie has been making – rather than hypocritical or tacked on.

This may sound complicated; now, not only do you have to worry about larger character arcs, you have to manage them moment by moment, but that’s not how Yorke sees it. Instead, he argues that this approach actually simplifies story structure. How? Through fractals.

Fractal structure

Okay, bear with me here. In order to understand Yorke’s point, we don’t really need to understand fractals in mathematical terms. All we need to understand is that a fractal is a shape that’s constructed in such a way that it looks the same at any level of magnification.

Imagine, for example, using regular Lego bricks to construct one, much bigger Lego brick, and then using several of those bigger Lego bricks to construct a huge Lego brick. If we work to an exacting scale, then the bigger bricks don’t work differently to the regular bricks, they just differ in size. If it takes (let’s say) 133,000 small bricks to make a big brick, we know it must therefore take 133,000 big bricks to build a huge brick, because even though everything’s bigger, we’re still making the same shape from the same shapes. In short, when it comes to fractals, the way you handle the small things dictates how the big things turn out.

As we’ve already discussed, Yorke imagines change occurring incrementally, with a character’s larger arc emerging from lots of smaller decisions. In this way, Yorke’s change is fractal – the character keeps making small changes over the story and, when you zoom out and look at their journey as a whole, that adds up to them making the same change on a larger canvas.

But Yorke doesn’t imagine that this fractal approach to progress is only happening on a character level. Instead, he describes stories themselves as fractal constructs.

Stories are built from acts, acts are built from scenes and scenes are built from even smaller units called beats. All these units are constructed in three parts: fractal versions of the three-act whole. Just as a story will contain a set-up, an inciting incident, a crisis, a climax and a resolution, so will acts and so will scenes. The most obvious manifestation of tripartite form is in the beginning, middle and end; set-up, confrontation and resolution. … What’s fascinating is that micro versions of the very same structure are performing exactly the same function on a cellular level. Stories are formed from this secret ministry; the endless replication of narrative structure is going on within acts, and within scenes.

– John Yorke, Into the Woods

This may sound a little heady, but in practical terms, it means that adopting Yorke’s approach isn’t a matter of trying to do every little thing at once. Instead, it’s about understanding that the small stuff shapes the big stuff. Get the small stuff right and it’ll add inherent structure to everything else; be true to your characters and themes on the small scale, and you’ll already have done half the larger scale work. Do the opposite – attend to the big stuff and expect the small stuff to just work itself out – and you’re doing a lot more work for a far less cohesive piece of writing.

Narrative symmetry

Our final big idea from Yorke – though not the last he has to offer – is that of narrative symmetry. If stories are fractal, with the smallest unit of change building to the largest, it makes sense that there’d be similarities in the overall shape.

This is something you might recognize from our article on quadrant theory, where a satisfying story arc is created by ‘splitting’ ideas and reflecting them against each other, so that each segment of a story reflects the others.

Yorke takes things further, arguing not that you should create a story by reflecting its component parts again and again, but that if you’ve achieved narrative perfection, this will happen all on its own.

If you take any archetypal story and imagine folding it over on itself at the midpoint, it’s possible to see with far greater clarity just how great story’s aspiration for symmetry is. Not only do the first part of act one and the last part of act five mirror each other, but act four becomes a mirror of act two, and one half of the third act, bisected at the midpoint, becomes a mirror image of the other. If you take any archetypal story and imagine folding it over on itself at the midpoint, it’s possible to see with far greater clarity just how great story’s aspiration for symmetry is. Not only do the first part of act one and the last part of act five mirror each other, but act four becomes a mirror of act two, and one half of the third act, bisected at the midpoint, becomes a mirror image of the other.

In a second act, protagonists move towards and embrace commitment; while act four works the other way: faced with overwhelming odds, the commitment is tested and as the worst point nears, abandonment is considered. … Act one and act five, act two and act four and both halves of act three – all echo and mirror each other around the midpoint. Further, in an absolutely archetypal story, the crisis in act two will work like an inciting incident – directly related to its mirror image, the crisis point in act four.

– John Yorke, Into the Woods

If you’re deliberately writing incremental change and applying an understanding of fractal storytelling to build from the ground up, this type of symmetry will be natural enough that Yorke describes stories aspiring towards it. Of course, there are still conscious decisions to be made – moments where you can help symmetry bloom.

If Daryll is the one who is slighted by Thelma at the end of act two of Thelma & Louise, then at the end of act four Darryl will be playing a significant role in tracking Thelma and Louise down; Rosencrantz and Guildenstern attend Hamlet in act two; in act four they die. At every level it should be possible to detect the same structural relationship.

– John Yorke, Into the Woods

Yorke is the first to point out that not every good story needs narrative symmetry, but he observes that it’s the ‘perfect’ form of narrative; so much so that many writers achieve it without deliberately seeking to do so.

The advantage of such symmetry is obvious – it ensures that a story is always ‘about’ its central concerns, creating a natural barrier against disappointing or disconnected endings. William Goldman’s Marathon Man, for instance, is a great book with a disappointing ending in which the historian protagonist adopts an action-hero, take-no-prisoners attitude that feels disconnected from the rest of the story. Up until that point, the story has been about plans within plans, the consequences of dark choices, and moments of triumph coming from quick-thinking under pressure. When it ends with a vengeful, cold-blooded murder, the reader is left with the discomfiting feeling of an unfinished song – the story doesn’t reflect its own themes, and so it offers dissatisfaction. In the movie adaptation, the ending was changed slightly, making it so that the villain’s death is caused more by his own machinations than by the hero’s tough-guy heroism; this is the version of the story that people still talk about.

So, what are you supposed to do with this information? First, keep in mind that this type of symmetry is a good sign – the sign of a balanced story – and that it will often appear as lucky happenstance. An idea or character will repeat, a decision will ripen into consequence, and you’ll be presented with the perfect counterpoint right when you need it. This isn’t luck; it’s your ability to recognize the most pleasing shape the story can take. When symmetry occurs, see it as the excellent sign it is.

Second, you can use symmetry to help plot new stories and interrogate existing stories that aren’t working. If a character’s appearance in the story isn’t symmetrical with their exit, if the placement of a consequence doesn’t really match where you had your character make the attendant choice, try playing around with your plotting until you have symmetry. Not every story has to be a perfect reflection of itself down to the molecular level, but as Yorke observes, this type of symmetry feels ‘right’ to the reader. If your story currently feels ‘wrong,’ it’s worth considering this as one solution.

Into the Woods, without delay

John Yorke’s Into the Woods is a cohesive work that offers a lot of complementary observations about writing great narratives. If you can see a glint of promise in the theories described above but you’re not quite sure how to apply them, it’s worth picking up the full work and encountering them in their native context.

The key thing to understand is that narrative exists on many different levels. There’s little that a satisfying story does that a satisfying scene doesn’t need to do, and since stories are ultimately just a collection of scenes, it makes sense to build from the ground up. Surprisingly, as Yorke points out, this isn’t just a case of having solid foundations, but rather of shaping the whole by shaping the parts. Do that in the right way and a story will reflect and echo itself down to its most fundamental level, creating an experience that’s engaging, moving, and satisfying, even if readers can’t explain exactly why.

What do you think to Yorke’s theories? Let me know in the comments, and check out A Three-Minute Guide To The Snowflake Method By Randy Ingermanson and The Quadrant Method Is The Key To Amazing Storytelling for more great ideas about what makes for a satisfying narrative.