What is a man? If you believe Dracula in Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, the answer is ‘a miserable little pile of secrets’. Far be it from me to question the dark lord (again), but if you’re going to try and write a convincing male character then there might be a bit more to it.

I’ve written before about how difficult it can be to write outside your gender, but in fact it’s difficult to get a grip on any character’s personal experience and expression of their gender. Compare, for example, Pride and Prejudice’s uptight but upright Mr. Darcy with the scummy, womanizing Sam Spade of The Maltese Falcon. Compare either to the kind, imaginative Haroun of Haroun and the Sea of Stories, Patrick Bateman of the appropriately named American Psycho, or secretive, heartbroken Patrick from The Perks of Being a Wallflower.

Could it be that these male characters, so different in their expressions of what it means to be a man, are reacting to a similar set of experiences and values? Surprisingly, the answer is yes, and by understanding how expressions of gender can be so complex, authors can write far more realistic men than they might ever have suspected.

Gender performativity

The term ‘gender performativity’ was coined by philosopher Judith Butler, and is used to describe a theory of what gender is, and how it influences us, that many authors will find revolutionary in terms of how they craft their characters.

Butler suggests that society’s concept of gender is prescriptive rather than descriptive – it creates a set of expectations and rules that define our behavior, rather than just being an observation of natural behavior. According to this theory, men are less emotionally expressive than women because they have grown up understanding this as the norm, rather than because of an inherent and gender-wide impulse towards stoicism.

Whether you subscribe to this theory or not, it foregrounds a truth that is essential to writing a complex male character; a man’s expression and experience of his gender is a reaction to how society defines that gender. Certain attributes and behaviors are understood as ‘masculine’, and in his everyday life a man is constantly reacting to that understanding. He is, in other words, comparing himself to an ideal man.

The ideal man

The ideal man is a theoretical individual – a man who embodies perfect and unfaltering masculinity. This fictional construct is seen to define the male gender, and is an essential component of men’s experience of gender.

In effect, men construct their own personal masculinity in reference to their version of the ideal man. They ask – sometimes consciously, sometimes unconsciously – what this idealized figure would do in a given situation, and judge their own actions in comparison. That’s not to say that every man does what the ideal man would do, or that every male character should behave as the ideal man. Remember that the ideal man is a point of comparison – if a man is in a situation where he can fight or run, he makes his decision while knowing what his version of the ideal man would do. He may fight or he may run, but if he fights then he knows he has lived up to this idea of masculinity, and if he runs then he understands he has failed to live up to the ideal. This is why a man confronted with impossible odds may make the sensible decision to run but still feel he has done the wrong thing – he has failed in comparison to the ideal.

Real men, and your male characters along with them, can be understood via their relationship to the ideal man. This is gender as a form of absolute morality – what the ideal man would do is often treated as the right thing to do. Understand how your character imagines the ideal man, and how they understand their personal masculinity in comparison to his, and you’ll understand exactly how they feel in any given situation. Since that’s the case, it might be useful to know a little more about how the ideal man behaves…

Defining ideal masculinity in writing

Much of literature is given over to considering what it means to be a man, and while there’s no definitive account, Rudyard Kipling’s If comes pretty close. The entire poem can be read here, but it’s so popular that the extract below may be all it takes to jog your memory:

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you…

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss…

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with Kings — nor lose the common touch,

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you,

If all men count with you, but none too much…

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And — which is more — you’ll be a Man, my son!– Rudyard Kipling, If

The poem celebrates traditional concepts of masculinity, lauding attributes such as:

- Stoicism,

- Bravery,

- Pragmatic thinking,

- Capability,

- Isolationism,

- Leadership,

- Physical ability.

These are the qualities of the ideal man – the standards which influence your character’s behavior and worldview. They’re powerful motivators, but remember that your character experiences them through a middle man. It’s not that every male character is striving to be brave, stoic and able, but that they understand that these qualities are what society expects of them.

This may mean a character tries to be brave, but it may also mean that a character who knows they are cowardly is especially sensitive about this being discovered. It may mean that a character will go out of their way to confirm that they are brave – this is the case with Marty McFly in Back to the Future Part II, who is talked into a deadly race when a rival brands him a ‘chicken’. Marty’s ideal man isn’t afraid of anything, and when an antagonist suggests he does not live up to this ideal, he jumps into a foolish action in order to prove him wrong.

It’s important to understand that these standards, compelling as they are, aren’t something the narrative has to agree with. It’s entirely possible to write a story where the character holds a certain idea of masculinity as the ideal, but the narrative suggests something different. This is the case in About a Boy; musician Will Freeman begins the story with a strict isolationist attitude, believing emotional attachment to be a dangerous weakness.

All men are islands. And what’s more, this is the time to be one. This is an island age… With the right supplies, and more importantly the right attitude, you can become sun-drenched, tropical, a magnet for young Swedish tourists.

– Peter Hedges et al, About a Boy

This changes, however, when Will comes into contact with vulnerable schoolboy Marcus Brewer. Will protects Marcus from bullies, and is drawn into meeting, and caring about, more people through his efforts. The story suggests that Will’s ideal man is flawed, and that Will is much happier once he allows his experiences to change his concept of masculinity.

Will’s ideal man gives him an idea of what he ‘should’ do, and influences decisions which would not otherwise make sense. Why would a man eschew real emotional connection? A lazy reading would suggest he’s incapable of establishing it, but Will’s status is clearly a choice. His journey isn’t learning how to be around other people, but learning that his conception of the ideal way to be is flawed.

This is something you can apply directly to writing male characters – how do they imagine the ideal man, and how do they imagine they live up to, and fail to live up to, their idea of him? When you consider your male characters’ decisions, focus on what parts of the ideal he is trying to emulate and the perceived failings for which he is attempting to compensate.

Remember, also, that some male characters may abhor society’s idea of the ideal man. They may go out of their way to flout this perception of masculinity. Even here, however, their self-perception still exists in contrast to the ideal. A male character who embraces his emotions is still aware that society’s ideal man is stoic – he has either come to terms with not meeting this standard or he remains conflicted.

This relationship between the character’s ideal man and his actual behavior is key to his point-of-view and all his decisions, but if the ideal man is shaped by wider societal attitudes, then how can he provoke such different behavior in different characters?

Male psychological narratives

Kipling’s poem doesn’t touch on sex or violence in great detail, and yet they’re two of the most frequently addressed aspects of masculinity. They are, really, just extensions of the blanket ‘capability’ a man is expected to have – both things to be ‘good at’ – but also seem to run counter to attributes such as stoicism and isolationism. This begs the question of how one character’s understanding of the ideal man could lead him to avoid violence, while another’s could lead him to seek it out. In other words, how do the hero and villain differ in their understanding of masculinity?

Often, in fact, the broad definition of masculinity is something which characters share. What differs is their relationship to the ideal, the emotions that this stirs up and the masculine narrative the characters imagine to be at play.

One near-perfect example of a masculine narrative is Jack Shaefer’s famous cowboy story Shane. Shane is a gunslinger who goes to work on a ranch, seeking to leave behind a violent past and attain solitude. Unfortunately the local gang have targeted his hosts, and Shane is forced to engage in an orgy of violence to set the situation right. What’s more, Shane is so attractive to women that the farm owner’s wife quickly falls in love with him, and Shane leaves the farm rather than break up the family who own it.

Here, the narrative is constructed so that Shane is all things. He is stoic to a fault – has changed his life to avoid violence – but when he is forced to fight, he is deadly. Likewise, he is intensely desirable and yet too honorable to act on it. Studied in detail, Shane is a near-impossibly perfect man. Even when being praised by other characters, the paradoxical nature of his being is difficult to escape:

“He’s dangerous all right,” Father said it in a musing way. Then he chuckled. “But not to us, my dear… In fact, I don’t think you ever had a safer man in your house.”

– Jack Schaefer, Shane

This is the example of one incredibly popular masculine narrative – the nonviolent stoic who is forced to enter into combat. The key to understanding how this same narrative can influence characters in very different ways is in realizing that the terms which make it up are subjective.

In Hydra Ascendant, the human protagonist finds himself in combat with the vampiric Baron Blood. Blood is preparing a plan which would place humans under the thrall of vampires, creating ‘a feast eternal’ that would allow vampires to thrive as the planet’s dominant species. Blood says:

Nature demands we kill any who bar us from our tribe’s needed resources. A true man would kill a nation to provide for his family.

– Rick Remender, All-New Captain America: Hydra Ascendant

While Blood’s plan is catastrophically villainous, his words highlight that he is engaged in a nearly identical narrative to the protagonist – both believe they are fighting to protect their people, and are able to justify extreme actions on that basis.

This is often described as ‘toxic masculinity’, where a man’s perception of his situation – and what the ideal man would do in his place – drives him to redefine immoral acts as the right thing to do, or as what is expected of him by society. A less extreme example might be the man who cheats on his wife, seeking out the sense of sexual ability that will bring him closer to his ideal man. At this level, the character’s need to establish an acceptable sense of self can be as insistent a drive as any other – a character who feels deprived of a deserved or badly desired sense of masculinity may behave as extremely as if his life was under threat.

The ideal man can therefore inspire heroic feats and acts of unspeakable evil, all depending on how the character frames their situation. Knowing this can help to give even the most diabolical character a cohesive worldview, or inspire seemingly illogical or dangerous acts from seemingly normal men.

There’s a lot of theory behind how masculinity is constructed and how it’s performed, but for authors it’s also important to think about the most basic levels of practical application.

Male dialogue and body language

The ideal man is stoic but he’s also an incredibly capable leader. This means that if you’re trying to portray the perfect man, body language and speech should be basic, insular, but packed with meaning. Generally, in this style of writing, when a man’s physical actions are described, it’s because they’re particularly effective or evocative.

Parker couldn’t tell yet whether it would be best to claim to knowing nothing or everything, so he went on waiting.

Younger had been trying some rudimentary kind of psychology, because now he said, “Or is it here? Do you know for sure it’s here? How come you were digging in the cellar?”

Parker shook his head, but didn’t say anything.

– Richard Stark, The Jugger

Here, a single shake of Parker’s head shows that he is unwilling to talk. It’s a response that’s cool under pressure but also effective – his opponent doesn’t press him or force him to deny again. Parker is a version of the ideal man, and so his communication is clear and absolute.

As with everything else I’ve described, however, the ideal man is just a concept of which more complex male characters are aware. This is the model of communication that your male character strives for, is conscious of not meeting, or actively rebels against. This may mean he over-explains, seeking the ideal of being totally understood, or is accidentally brusque. He may be overly verbose, conscious that he is not trying to be the gruff he-man, or grow irritated when questioned. The outcomes are varied, but they can be kept consistent and understandable by understanding the ideal against which they are defined.

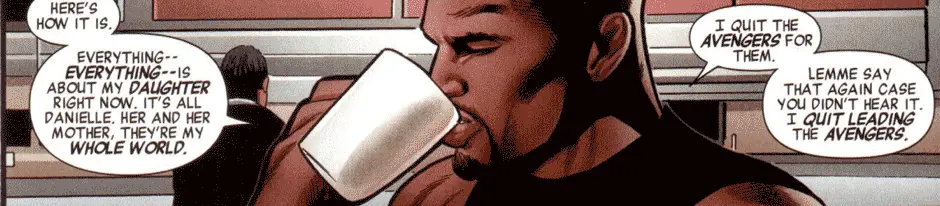

Graphic storytelling offers a host of good examples, as body language choices are immediately visual while remaining static. Marvel comics character Luke Cage acts as a great case study in this medium, showcasing the dialogue and body language choices used to portray an ideal man. Cage has many idealized male attributes – he is a leader, a concise speaker, and possesses bulletproof skin and enhanced strength. Cage can literally take a bullet, adding great weight to any attempt to end things peacefully; he chooses nonviolence even though violence would usually guarantee his success. As an (at least partially) idealized man, Cage’s speech and movements are simple but effective:

– Al Ewing and Greg Land, Mighty Avengers

Here Cage expounds on his worldview, vowing to take action but remaining stoic while doing so. While extolling his commitment to family and detailing a major life choice, Cage sips coffee, an accepted visual shorthand for casual behavior. As he states his intention to change the world he has one eyebrow raised – an incredibly mild gesture given the impact of his words. Cage’s words have intense personal and emotional relevance, but Ewing uses repetition to reinforce this rather than having Cage be more emotionally expressive in other ways.

This is the body language and dialogue of the ideal man – a huge subconscious influence on male characters. This is the accepted standard for confidence; a way that a confident character might behave, having been taught that it properly expresses their surety, but also something that a less-confident character might try to establish authority.

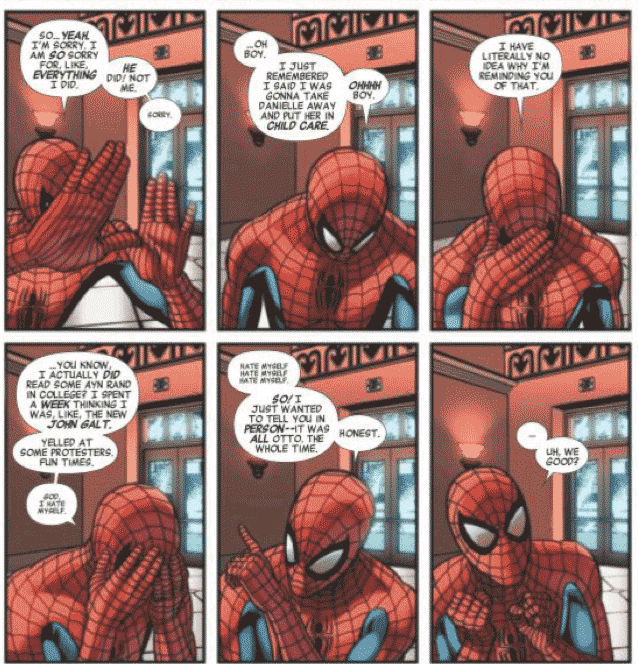

In contrast is the scene below, where Spider-Man attempts to apologize to Cage:

– Al Ewing and Luke Ross, Captain America and the Mighty Avengers

Here Spider-Man adopts body language and dialogue that stands in direct contrast to Cage’s. He performs large, frequent movements and rambles, having difficulty making his point. This, however, is not simply a failure of masculinity. Spider-Man is abasing himself before Cage – he acts counter to the masculine ideal because he is both consciously and subconsciously submissive. He places Cage in the dominant position, making it easier for Cage to be the ideal man (one who Spider-Man hopes will be magnanimous enough to forgive him).

This brings us to the final, and perhaps most important, aspect of masculinity to consider when writing male characters.

Masculinity as a dialogue

One of the defining traits of masculinity I listed above is ‘leadership’. Because of this, male characters will generally have some appreciation of the power relationships in any given group, or will make attempts to understand those relationships.

Again, this does not mean that a male character will always be in charge, or always try to take charge, but it means they will be aware of whether or not other characters are trying to do so, and of where they stand in the hierarchy of a group. They may be comfortable with a lower position or chafe under orders, but they will have a particular awareness of where they stand, and a sensitivity to occurrences that may alter the status quo.

In Hellbent, Anthony McGowan details his teenage protagonist’s journey through hell. Throughout the book, the character pretends he has no knowledge of why he’s there, but the conclusion of the story sees him admit his single greatest sin; the mistreatment of a bullied classmate.

I certainly didn’t join ‘the line’. And what was ‘the line’? Every few days the school thugs would make Jason walk slowly down a line of boys – they tried to make everyone join in – taking a punch or a slap from each person as he passed. The ‘winner’ was the one who made him cry…

Sometimes I caught [Jason] looking at me. It was unsettling. I felt bad because I thought he might want to join in with my gang, play footie… But what did he think I was? A social worker? I’d fought hard for my status as maybe the second or third coolest kid in the year… Next time, I thought, I’ll join the line. It’s that or get infected with monkey fever.

– Anthony McGowan, Hellbent

Here the character makes a horrifying moral decision not out of cruelty, but because he fears for his own place within the group. He is not attempting to gain anything, but simply to retain his standing and the regard of his peers.

The character might have made another decision, but the point is that he would still have considered his place in the schoolyard. Likewise when a male character is mocked, challenged, corrected or praised; they may react to it in many different ways and for many different reasons, but they will always factor in how it influences the way in which they are seen.

In A Visit from the Goon Squad, Jennifer Egan writes several male characters who are intensely aware of the way in which they are perceived.

‘You don’t want to do this,’ Bennie murmured. ‘Am I right?’

‘Absolutely,’ Alex said.

‘You think it’s selling out…’

Alex laughed. ‘I know that’s what it is.’

‘See, you’re a purist,’ Bennie said. ‘That’s why you’re perfect for this.’

Alex felt the flattery working on him like the first sweet tokes of a joint you know will destroy you if you smoke it all… Alex felt the sudden, riveting engagement of the older man’s curiosity.– Jennifer Egan, A Visit from the Goon Squad

Here the characters make decisions not just according to their own sense of masculinity, but in an attempt to manipulate that of the other man. They flatter each other, and Alex is even aware that an older man’s curiosity validates his masculine identity. Bennie wants something, and is trying to both leverage his own masculine power as an older, more successful man, and to frame what he wants in terms of a masculine narrative Alex might accept.

This is the next level of writing masculinity – not just being aware of how masculinity acts as a drive and influence on a character, but making that character aware of how masculinity can influence the behavior of other characters.

Writing male characters

There is, of course, no one way to write ‘a man’. What I’ve detailed above is instead a way to get into a male character’s head and identify some of the key motivators that may drive him to make one choice or another.

As Judith Butler rightly pointed out, gender may be performative but it is not separate from ourselves. We’ve been performing since we were born, and masculinity is no easier to study as an isolated quality than race or sexual preference. Indeed, masculinity is bound up in these things and should be considered alongside them.

Safe ‘truths’ like ‘men can’t process their emotions’ are inaccurate and, worse, they’re useless to authors. Instead, consider that men have been told that not engaging with their emotions is key to masculinity. A male character who just doesn’t have emotions is a joke – less than two-dimensional. More interesting, and more realistic, is the character who has strong emotions but suppresses them (and why he does so) or the character who has rejected the masculine standard and chosen to express what they feel. Consider, also, the character who tries to suppress their emotions but fails, or the character who has suppressed their emotions for so long that they have trouble bringing them to the fore.

These characterizations ask questions and let characters grow. Why might a character be trying to excavate long suppressed emotions, and why did they suppress them in the first place? Perhaps their father was unemotional, a masculine ideal, but now they want to engage more fully with their kids. Perhaps that suppression led to unhealthy behavior and they want to change. Perhaps, perhaps, perhaps.

You’re probably expecting me to end on the advice to ‘write a character first, and a man second’, but I’m not going to. Gender is an inextricable part of who we are – it’s something that’s baked into our identity, not sprinkled on once we’re already fully formed. To not think of a character as a man is to ignore one of the most formative qualities that would define their personality. What I would suggest is to explore every nook and cranny of your character’s identity, and to spend as much time as you feasibly can mixing each part of it together, finding their unique backstory.

Do you have a favorite depiction of masculinity in fiction, or do you think it’s the least important part of a character’s world view? Let me know in the comments, or check out How To Write A Damn Good Woman and Why Authors Need To Take Care When Writing The Other Gender for more great advice on this topic.

33 thoughts on “How To Write A Damn Good Man”

Excellent piece, and a good angle to consider when writing characters.

One error, though: you say “proscriptive” when you mean “prescriptive”. To “proscribe” something is to forbid it. To “prescribe” something is to require it. It’s a common error – I’ve seen Samuel R. Delaney make it – but it is an error.

Hi Mike,

Thanks very much for your comment, and for catching that typo. It’s been corrected above.

Best,

Rob

Hi Robert.

This is an excellent piece, and I’m in full agreement that one’s gender identity is baked into life at all times. I am, however, fairly astounded that a discussion of masculinity and the perfect man did not include Bond, James Bond. Flemming’s badass spy with a weakness for women probably inspires men daily to ask, “What would JB do in this situation?” Okay, maybe not daily. But every time I’m strapped to a nuclear warhead with supermodel, that’s my go-to.

Thanks!

Mark

Hi Mark,

Thanks for the kind words. James Bond is a great example of masculine narratives in fiction. Interestingly, I believe he was originally created as an amalgamation of many of Ian Fleming’s wartime associates,

Best,

Rob

Excellent example as in “Bond, James Bond”

Hi Rob,

Fantastic article. It’s come at just the right time. It’s always challenging building the layers of a male character, but comparing him to an ‘ideal guy’ seems like an effective way to make his actions plausible in all situations. Thanks for the advice! 🙂

Milan

Hi Milan,

No problem, I’m glad it’s useful. Characterisation is so difficult – there are always going to be blindspots when a writer invents a person – but finding consistent behavioural traits is one of the best ways to nail it.

Best,

Rob

Wow, I have no words… I loved your article and how you went deep into the subject. Very enlightening, and since I like psychology, it was a joy to read. Thanks for sharing.

Hi Nicole,

Thanks very much – what a great reaction. I’m glad the article was useful.

Best,

Rob

Fascinating. Thank you for sharing.

My pleasure, Karyn.

What about Clint Eastwood? His leading roles in movies like, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly I think he’s an ideal man. I really liked this article!

Hi Alina,

Clint Eastwood is a fantastic example – thanks for commenting.

Best,

Rob

This article has helped me reconsider how I’ve written male characters and has affirmed some of the other choices I’ve made. Basically, you’ve pinpointed, what has been up to now, elusive. Greatly appreciated.

My pleasure, Jubilee . Thanks for commenting.

Thank you for this excellent article. It has given me actionable advice and insight that I will use. Much appreciation.

Thanks for the feedback, Sue. I’m really glad the article was useful.

Excellent, thank you. There’s so much more to men than what society prescribes.

Hi Lorena,

Thanks for commenting – I’d certainly like to think so.

Best,

Rob

Great article! Thank you so much for sharing these tips. I’m sure the male heroes of my romances will benefit from them. 🙂

PS: An example for your “deadly stoic” ideal type: Tom Stall (Viggo Mortensen) in “A History of Violence”.

Hi Ana,

Thanks for commenting, and with a fantastic example. Perhaps the ultimate ‘great at violence but trying to escape it’ character.

Best,

Rob

I have a book that I’m writing, and I’m thinking of doing each book in a different point of view, i.e., that there is going to have a book from Tanis’s male friend (Possibly boyfriend, I’m not sure yet, I haven’t even gotten a name for him) and this helped. Still not sure if I want to do the “Multiple character views” thing.

Hi Annabelle,

Thanks for commenting. What you describe is an interesting approach, I hope the articles below will be useful in considering it further.

//www.standoutbooks.com/choosing-right-perspective/

//www.standoutbooks.com/avoid-head-hopping/

Best,

Rob

Do you have one about writing female characters? I mean from a similar standpoint as in examining the ideal woman. Admittedly, it might be harder to find examples of the feminine ideal written by women but I think they do exist. (Also, I suppose feminism has changed the ideal woman to be extremely complicated, but she still does exist)

Ah I see that you seem to have one my bad!

Hi Emily,

Not at all – the articles below may be of interest on this subject, and I’ve made them more prominent in the article above.

//www.standoutbooks.com/how-a-damn-good-woman/

//www.standoutbooks.com/writing-the-other-gender/

//www.standoutbooks.com/writing-strong-female-characters/

Best,

Rob

Thank you sir

The article is worth understanding.i wanna to ask one thing about it,The masculinty framework which you have discussed in the article

Stoicism

Bravery etc is drived from which theory of masculinty?

Thanks in anticipation

Hi Faria,

Thanks for your question and kind words. The stereotyped masculine qualities I mentioned are drawn from a general overview of current Western gender theory. As I mentioned, the suggestion isn’t that these qualities are inherently or exclusively masculine, but that there’s a historical precedent of them being used to codify what masculinity is and how it ‘should’ be expressed.

Best,

Rob

I write my male characters based around the idea that “a real man is someone who stands up and does the right thing regardless of the cost to themselves.” The more likely they are to do this the more masculine they are. The “right thing” is different in every situation. At one point it might be protecting your family from a home invasion and at another point it might be knowing to not get bated into a fight. Being a man in anything I write never means, lack of emotion and always willing to solve a situation by physical force. Sure, those things may be necessary, but they’re not what makes a man a man…it doing those things when, and only when, they’re the “right thing.” And the harder the “right thing” is, if the man steps up and does them, the more of a man he is. Showing emotion, asking for help, NOT being an island, can and often are the “right thing.” I want to put male characters in positions where they have to do those things and if I want them to be real men, I have them stand up and do them. Knowing when to back down from or when to not even get involved in a fight is one clear example I use (when it fits the story) to show a man being a “real man.” Sure, brute forcing your way through a problem head on shows a man being a man and I do have male characters do this, but if it’s not necessary then it takes a real man to know this.

You’ve saved my character, this article is brilliant! I’m trying to write a YA fiction that will attract male readers as well as female ones and give them both strong role models, but my male protag’s motivations have felt so one dimensional. I’ve done more fleshing out of this character while reading this article than I have in years of idly tinkering with this story, thank you!

Very, very much my pleasure, Leslie. Glad it was useful.

– Rob

Thanks so much for the insightful article. I’m in the planning stages of my fantasy novel and the one male character which was supposed to be an “extra” is turning into the protagonist.

This has made me really nervous because of the masculine perspective but I feel much better about placing him in front.

For obvious reasons your content on this page is spot on for various reasons. It steers away from the usual pitfalls and traps most fall into- getting defective alternatives. Thank you!